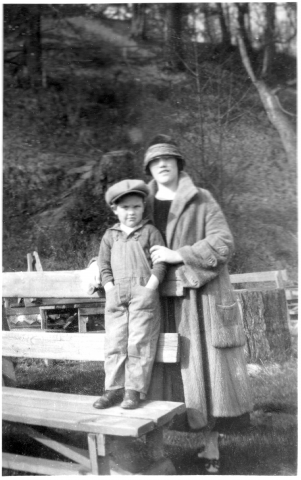

Richard "Dick" Harris in service in Lewiston, Idaho, in 1942. Hand colored image.

From February to October 1945, Richard Daniel Harris flew C-46 military transport aircraft between India and China through the Himalayas in support of the war effort against Japan, carrying every kind of material or personnel over "the Hump." Only a young man only in his early twenties, he eventually made eighty-one trips over the Hump.

Richard D. Harris was born August 30, 1921, in Seattle, WA. Dick grew up on Alki Point in the 1920's, riding the streetcar and attending school at Holy Rosary in West Seattle, where he was one of 12 original altar boys at the christening Mass at the new church with Bishop Shaughnessy. He graduated from O'Dea High School in 1939, with a basketball scholarship to Seattle College (now Seattle University). After his freshman year, Dick transferred to the University of Washington to focus on pre-law and joined the ROTC (Reserve Officer Training Corps). In the Summer of 1941, he met the girl of his dreams, Bernice (Bea) Anderson, at the Eagles Auditorium in Seattle, where Jimmy Lunceford and his Big Band were playing. Once she taught him to dance, they were married--between sessions of flight training--on May 21, 1943, their love story eventually spanning 73 years.

-=-=-=-=-

Below is some Dick's own recounting of a bit of his story (compiled and edited by Patrick Lucas from various first-person narrative sources supplied to Remembering Shared Honor by Mr. Harris, along with resources such as public interviews he gave, and the eloquent, heartfelt obituary written by his children):

INTO THE WILD BLUE YONDER

World War II was different from other wars I've come to know. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor every red-blooded American felt personally attacked. As a result, the average American youth needed little encouragement to enlist in the defense of his country. I was caught up in this same patriotic euphoria. Within weeks following December 7, 1941, Ron Clynch, my best friend all through grade school, high school and college (we were both enrolled at the University of Washington at the time) went to the Army Air Corps recruiting office to enlist as Cadets in primary flight training. I flunked the physical because of my poor eyesight (20/30 in my right eye). Ron got accepted and I went home very disappointed. Within three months Ron was back home with me. He had flunked out of flight training. So now what do we do? We got a couple jobs doing defense work, building housing for the great number of defense workers coming into the Seattle area. But we weren't content with that. Ron heard of openings in a flight training program called "CPT", Civilian Pilot Training. He also heard the physical and flight training was not as rigorous as the Cadet program. So we both went down to enlist in that program. We went home after giving them all the information they wanted as well as taking the physical, which I passed this time including the eye exam. I had practiced reading the eye chart with my left eye (the good one) and then doing the test with my right eye. I continued to excel at all my future eye exams because I always did the left eye first no matter whether the examiner asked me to do my right first. This gave me a chance to see the chart first with my left eye and then I would own up to not being able to tell my right from my left but I had managed to get a look at it first with the left and memorize it so I had no trouble doing the right "first". About two weeks after our exams, we heard back from CPT, I was accepted, and Ron was not (because he had washed out of the Army Cadet program).

I lived in West Seattle at 4155 38th Avenue S.W. (phone number We 5511) when I was ordered to Lewiston, Idaho to begin my flight training on July 3, 1942. There were about twenty in our class. We were housed in the dormitories at Idaho State College in Lewiston and we took our flying lessons at Zimmermann Flight School in Clarkston, Washington which was just across the Snake river that divides Idaho and Washington. Don Wolfe was my primary instructor, and I soloed a Piper Cub J3 on July 15, 1942 after nine hours of instruction time. I completed the course (Primary) without incident and started Secondary training on September 7th and completed it on November 4th (guess whose birthday that is).

The students who completed both courses on time were then sent to Yakima for training in Instrument flying and Cross-Country flying. Kurtzer Flight Service was in charge of our training. He had an air service operation going out of Lake Union in Seattle before the war, but because of restrictions on all civil flying on the coast he had to move his operation to Yakima. He flew his float planes off the water in Lake Union and landed them on the snow in Yakima. We got started around November 16, 1942. completed these two courses of training on February 8, 1943. There was a delay in my training for over a month until March 24th when I was assigned to Prineville, Oregon to take an Acrobatic course which I completed on May 19, 1943 and was given orders to report to Randolph Field, Texas for my Instructor's course. This left enough time to get married on May 21, 1943 to my bride Bernice (Bea), starting a lifetime together of 73 years.

San Antonio was hot during the summer months I was there, and I finished on July 22nd with orders to start instructing Primary Cadets in Oxnard, California on August 4, 1943. This new batch of instructors of which I was part of now released the Army Air Corps officers who were instructing at this time to be called into another branch of the Army Air Corps. I stayed at Oxnard until March 27, 1944 when after 850 hours of instructing Army Primary I had a chance to get into something different and more exciting for me, the Ferry Command.

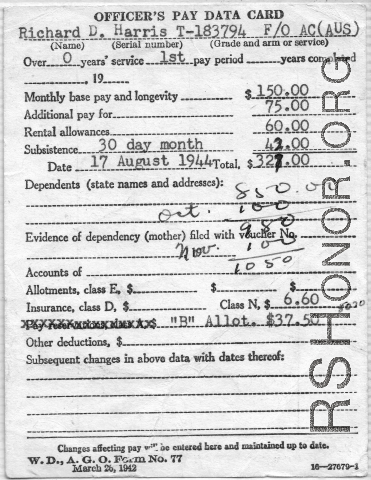

I received two months of furlough mainly to give the Army time to work out the details of this new program it had decided on where it would start a pilot out for a specific assignment, in my case as a transport pilot. I was sent to Deming, New Mexico for more instrument training and night flying instruction. This was finished in just under a month on June 24th. Then on that same date I started training in multi-engine aircraft in Douglas, Arizona. On August 4, 1944 I was commissioned a Flight Officer (T-183794), destined in a few months to be sent to India to fly the Hump (of course, I didn't find this out until later). I spent a couple of days at Long Beach Army Air Base and then was sent to Palm Springs Air base on August 9th. My new wife Bea and I had no complaints about that assignment.

While at Palm Springs my assignment was to ferry (deliver) new airplanes built in factories in Long Beach or Los Angeles to various places in the United States, where they would then be flown overseas to either Russia or England. I flew as pilot or copilot on airplanes to such places as: August 22 a B-17 from Long Beach, Cal., to Lincoln, Neb.; Aug. 24 a PT-22 from Palm Springs to Jackson, Miss.; Sep. 6, I qualified as an "expert" with the Carbine rifle at Palm Springs, this was required as I was in the Army; Sep. 10. an A-20, attack bomber, from PS to Montreal, Canada; Sep. 20 I did the same. After delivery I would return to Palm Springs by commercial airlines with the highest priority for seating. Oct.23 a B-26C from San Francisco to Lake Charles, La. Then it was on to Reno on Oct.30, 1944. Etc.

I had one of my biggest flying thrills while ferrying a P-38 to Wilmington, Delaware. I picked the airplane up at the factory in Long Beach and headed for Wilmington. On my way I stopped to refuel and lay over for the night in Texas at an Advanced Fighter School training center. When I landed this brand-new P-38 every pilot on the base turned out to see it and I was mobbed by those guys in training wanting to know how fast it flew, how it handled, what was the max speed and several other questions of this brand-new pilot and his brand-new plane. I delighted in telling them all about my experiences except for one item I had tried when flying it from Long Beach. I had it up about 10,000 feet and wanted to see how fast I could dive it. It was red-lined (not to exceed) at 425 mph, so I dove it 430 mph for the thrill of it. Remember, I'm only twenty-two years old at this time.

While at Palm Springs, I flew all sorts of military combat aircraft. I came in contact with several famous people, such as Howard Hughes the aircraft builder while I was in Reno, and he took me and a friend to dinner at the old Riverside Hotel. The friend was "Wrong Way" Corrigan, who told the New York airport tower operator he was going to Los Angeles and wound up in London, England. He was stationed with me at Long Beach when I was there before being sent to Palm Springs. He explained his mistake as "I turned the wrong way". He was suspended for one year from flying by the FAA, but the Army took him in without any suspension. I don't know if he ever flew again or not. Movie actors Patrick Knowles, Robert Cummings, and Richard Simmons were with me at Oxnard when I was teaching Primary Flight. They were also instructors who, on the side, were making movies as well.

We remained in Palm Springs until November 2nd, then I was sent to Reno for Hump flying instruction. Bea and I rented a quaint little cabin in a motel complex right in town, and Bea had a sun area on the roof where she could sunbathe, and I could spot her from the air when I flew over going to or from the airport. To this day I don't know if she sunbathed nude or not, but some of my flying buddies said they saw her once or twice when they flew over, as it was right in the landing pattern as you approached the field. Yeah right! When the winter rents went into effect at the end of September, we had to move, as we couldn't afford them. We went to Cathedral City with another couple, the Heinliens, and rented a small house. Both of us had a small child, and Mildred and Bea got along nicely. Hal had been in my class at Deming. I remember another flying buddy of mine, Benny Lapadula (Lap-a-du-la), complained bitterly when we moved. He said he missed seeing Bea on the roof...

At Reno I was instructed in in nighttime, instrument, and cross country flying for the C-46, Curtis Wright transport plane--built specially to fly at high altitudes and carry heavy loads, and used heavily in the China-Burma-India theater operations. So you didn't have to be a brain surgeon to know you were headed to India to fly the Hump. After two months and one hundred hours of instruction I received orders to report to the Floridian Hotel, Miami, Florida., for shipment overseas. I was given three weeks leave before having to report.

My wife, young daughter, and I made a hurry-up trip home to Seattle in the '37 Ford loaded with everything we owned. Then I flew to Reno and I was there until I had a couple of days off for Christmas, and then I flew to Miami for shipment overseas. In Miami I received all my overseas gear and "shots". Then it was off on my journey towards Chabua, India, and the 1332nd AAFBU, Foreign Service Station, Mohanbari, by way of South America, Africa, Tripoli, Cairo, Karachi and then Chabua. I arrived in Miami on February 4, 1945 and on February 10 I was already starting my journey.

My trip from Miami was in a C-54 transport, a four-engine plane recently delivered to the Army to carry passengers on long distance flights. It had a crew of four and thirty-five passengers (including myself and 10 other pilots) on board bound for India. Our first stop after leaving Miami was Georgetown, British Guyana where we refueled and spent the night. The next day we landed at Belem, Brazil to refuel and then off to Natal, right on the coast of Brazil, where we stayed a couple of days waiting for the weather to clear up a little on the Atlantic Ocean before we were cleared to Ascension Island, a small island in the middle of the ocean that was used for refueling.

The Germans had no airplanes in this area, but they did have submarines and they knew the radio frequency of the island "homing devise" signal. The U boats would surface and broadcast that frequency a few hundred miles off course and if by chance you picked up the "wrong" signal you could wind up having to land in the middle of the ocean instead of Ascension Island. Need I say we got the right signal, refueled, and eventually landed at Dakar on the west coast of Africa. From there we went to Casablanca, in north Africa (Humphrey Bogart' s movie). On to Tripoli where I saw my first prisoners of war, captured Italian soldiers (who were glad and thrilled to have been captured in order to get out of the desert fighting they had been involved in under the German General Rommel). They worked in the mess hall as waiters and were delighted to be there and to serve us. Off to Cairo, Egypt and the pyramids. Stayed a couple of days in Cairo to catch our breath and do a little sight-seeing. It wasn't long enough, and then we were in Karachi in the western part of India. We flew across India and while doing so saw the Taj Mahal on our way to Chabua in eastern India and in the Assam Jungle, famous for its tigers. That was where Frank Buck, the lion tamer of the US circus, got his tigers. After two days of fighting diarrhea, I was permanently assigned to Mohanbari about thirty miles west of Chabua. I stayed there until November 1945 when I was sent to Calcutta to await shipment home.

Some of my experiences in Mohanbari (Mo-han-berry) might be of interest. I spent the first two weeks in the transit officers' quarters awaiting the assignment of permanent living quarters, and I use that term loosely. I was also battling, for lack of a better word, my bout with diarrhea. Finally, both came to an end about the same time. My three other basha mates were: Alan Cunningham, a Captain whose home was in New Jersey, Bob Boswell a 1st Lt. from Georgia, and Harry Berd, a Flying Officer, like me, from Michigan. We really hit it off well all the time we were together. Alan and I were the camp Bridge Champions in those days I played Bridge. Bob was a nut about baseball and basketball, so he and I had lots to talk about. And Harry was my age and had gone through training with me at Reno.

We all shared a Basha, which was our home. It was a 25 x 20 foot slab of concrete, with four posts in each corner about six feet off the floor from which hung our walls of mosquito netting and canvas, the roof was V shaped made of straw about four inches thick. Inside we had four beds, one in each corner and two narrow four foot tables in the middle. We had one electric light hung from the ceiling and our beds were solid wood with canvas straps for a mattress, olive color sheets and blankets and a cotton filled pillow. The beds had mosquito netting tucked under the sheets, extending upward about five feet and tied to four posts at each corner of the bed. On top was a bamboo slab that was our shelf for our watches, wallets, pictures of loved ones, razor and shaving gear, plus whatever other valuables you wanted to put up there. Hanging on one end was our shoulder gun belt, with our 45-caliber pistol, which we had to carry with us every time we went on a trip to China. We all shared the services of a "bearer," a house boy (man), named Bean. He was twenty years old, married with two children. We paid him a total of $9 a month, twice what he was making in the tea fields. He made our beds, did our laundry, hung up our clothes, cleaned the basha and ran errands for us. Once when I was playing baseball and played the position of first base, I had him come along to the game and chase any wild throws thrown my direction. This was all for nine dollars a month, and he loved his job.

We ate in the officers' mess. Our menu was Spam and eggs for breakfast, Spam sandwich for lunch and roasted Spam for dinner. At every table there was a container of salt tablets and another container, the size of a sugar bowl, containing Atibrin, to ward off malaria. The salt tablets were so we would retain some water rather than sweat it all out during the Monsoon season. Incidentally, the Monsoon started around April and continued for about three to four months. More than 200 inches of rain would fall during that time, with temperatures in the 80's and 90's both day and night.

I started flying as a co-pilot for a month and a half, and then was assigned to an instructor pilot for about a week, to check me out as a first pilot. I was a first pilot for a few months, then became an instructor pilot, and later a check pilot who taught instructor pilots. Flying came easy to me through no fault of my own, which was fortunate...those assignments helped me endure the disappointment of the change orders issued by the General in command of the Hump directives for rotation. When I first came over you had to have 500 hours of combat time to be rotated back to the states. I figured I could get that time in by July and be home by August. A couple months after I arrived in the CBI, the general, a guy named Turner, raised it to 600 hours, so that was another month or two, then he upped it again a few weeks later to 650 hours, and all the pilots were "pissed off," to put it politely. Normally morale was pretty good at Mohanbari, but this cast a cloud over it for several weeks. Pilots were finding lots of excuses for not being fit for flight duty. However, after a while things were back to normal, and everything was SNAFU (Situation Normal All •_ucked Up) was the saying.

I averaged around 90 flying hours a month. That was about the top; some were much lower. In fact, Alan Cunningham, one of our basha buddies, averaged about ten hours a month, just enough to qualify for "flight pay" for the month, which was about $70 over our base pay. Mine totaled out at $370 per month. The only time I got more than that was once when I was alerted for a flight and to stand ready to go. I got in a craps game in the waiting area with some of the other guys waiting to "go" and when my call came to go to the flight line, I was $300 ahead and quit. That was another month's pay, so I stayed "quit" and can always say I made a little extra money in the Army.

I was sure glad I made pilot, as I had ridden with some weird pilots on a couple of my trips as a co-pilot. One guy in particular scared the hell out of me. On a flight in the middle of the trip over, we experienced some "icing" on our wings and on the blades of the propellers. Instead of using the de-icing equipment installed to try and correct the condition, he backfired the engines - one at a time - by cutting off the ignition switch to the engine. I'd never heard of that in all my training, and neither had any of the other pilots I ever spoke to about it. There was a loud bang and the whole plane shuddered when he did it. I guess it got rid of the ice, but I was so scared I really don't remember. I knew I never would fly with that guy again no matter what my orders were.

We never had just one plane assigned to us, like the pilots who flew fighters and bombers. We just flew the first plane ready to go with its cargo. More than once, you might fly the same plane, but it was just the luck of the draw. Each plane had its own Crew Chief, who was the main mechanic and knew his plane and its problems, if any. He made sure he had those problems fixed, because 1) he had to get his flight time in each month to qualify for flight pay, and 2) he might have to fly with the plane if the pilot assigned asked him to come along, just in case. The pilot always had the right to ask the Crew Chief to make the trip with him. Each plane had a name bestowed upon it by its Crew Chief One such name that I always remembered was "My Assam Dragon." Remember, we were stationed in the Assam Jungle area.

It took anywhere between 6 to 9 hours in the air to make a round trip from India to China. The weather was the major factor in determining how long the trip would take. Wind and icing were our biggest tormentors. Cloud cover was another main factor. Our loads weight wise were always the same: maxed out. Occasionally the Japanese bombers would bomb our main landing destination and cause us to change our course to another field. However, this occurred very seldom, and not at all during the last four months of the war.

Our cargo was everything you can imagine: Jeeps, trucks, bombs (500 pounds and less), ammunition of all kinds, food, gasoline in 50 gallon barrels, Chinese troops, tents, medical supplies, etc. My strangest load was not from India to China, but from China to India. It was a cargo of tea, of all things.

We would take-off in India, which was about 100 feet above sea level, and circle around in the Assam Valley until we reached 8,000 feet, and then head for the Himalaya ridge of mountains. There were three ranges, each separated by a river below that flowed down from northwestern China and into the ocean around Rangoon. Each range got a little higher as you flew towards your destination in western China. The first range was about 10,000 ft and the last range was around 12,500 ft. Then, most of the landing fields in China were around 6,000 ft, about the same as in Denver, Colorado. We had "homing signals" along the route that helped during good weather. But with the good weather you really didn't have much use for them. It was bad weather when they were needed and, of course, that was the kind of weather we had most of the time. And they didn't work very well. When we landed in China the coolies would unload our plane, and we would head for the mess hall and get our orders in for fried eggs. They had fresh eggs in China, while we never saw one in India, so it was always a "dozen egg" omelet. That had to last us until our next trip. We usually returned "home" empty, and as a result took the higher route back over the Himalayas, at around 16,000 to 18,000 ft. A round trip was about 1,000 miles.

I had two flights that stick in my mind to this day. The first was taking off from Mohanbari with a full load of pipe in fifty-foot sections. The pipe was to be used in the construction of the Burma pipeline being built by the Army Engineers, to carry fuel across the Himalayas alongside the Burma Road being constructed at the same time. I was going about 50-60 mph down the runway, gaining speed as I went to reach my takeoff speed of 80-90 mph, when the right front tire blew out. As the right wheel rim dug into the runway tar surface it caused the plane to veer to the right. I'd never practiced this before. The nearest experience I had was cutting an engine on takeoff and following the set procedure of backing off on the opposite engine to control the plane; however, with the wheel digging into the tar on the runway that practice procedure wouldn't work. So instead of just cutting down on the throttle of the left engine, I also had to increase the throttle on the right engine and climb on the left brake to keep the plane from spinning to the right. All that time I was thinking, "My God, the back end of this plane is filled with pipe and if I stop too soon all that pipe will be rushing forward, through its restraining bullhead into the cockpit." With all of it happening so fast I didn't have any time to pray, so those few extra prayers I said when I was younger were heard and everything came out ok.

The second experience was in China waiting to land at Kunming, the largest and best equipped airport of the five we went to in western China. The weather had worsened on our way over and the landing conditions were below the allowable limits. We had our choice of turning around and heading back to India, which meant throwing our load out to lessen our weight; or bailing out and let the plane crash some place; or waiting over Kunming for clearance to land. I asked the other two crew members what they wanted to do and they said, "You make the call." Before "making the call" I remembered all the previous training I had had in various practice sessions. First, in Yakima in a Link Trainer, a mockup of a cockpit with instruments similar to those in a regular airplane, but in that training we never left the ground or saw outside the cockpit. Next, in actual airplanes with an instrument instructor riding with me, but I was covered over, seeing only the instrument panel of the airplane, and not outside. I also had my training in Deming, New Mexico, and Douglas, Arizona, in multi-engine airplanes; and in Reno in the C-46 before going overseas; and finally, in Mohanbari with an instructor pilot with me. I had made instrument landings before in China under actual conditions, but they were all weather conditions which did not go below minimum conditions. This time it was the real thing, and we were well below minimum conditions with all the fog.

In a situation like that, the wind had to be calm, and the tower reported that it was (otherwise, there wouldn't be fog, but also the wind could throw off your timing and compass headings). Also, the radio reception had to be good, and it was. We picked up the radio signals "dit da" and "da dit," that were transmitted into four quadrants so that when the two signals met they formed a constant steady signal with a cone of silence directly over the radio transmitting station. So, everything was nearly textbook for making an instrument landing. The Gyroscope was set to the proper compass heading (we couldn't rely on our actual compass in this procedure because they lag and twist around for a few seconds whenever disturbed; a compass is really only a magnet floating around in a jar of alcohol that is attracted to the North Pole). The altimeter was set accurately to coincide with the outside barometric pressure. In a landing like that, you then put the airplane on a predetermined heading at a certain air speed, for a certain amount of time (maybe 55 seconds), letting down, losing altitude on the downwind leg of the landing pattern, until you make a left turn - usually about 90 degrees - for maybe 10-15 seconds, and then another 90 degrees into your final approach, letting down all the while, to a certain height until you could see the end of the runway. If the runway was not visible after a certain length of time, maybe 10 seconds, then you had to push the throttle full forward (power on the coal), give it the gun and get the hell up into the air - high enough to BAIL OUT. I had never practiced that maneuver.

So, when it was finally our turn and the clearance to land never came, I "made the call" and we started on down. The field remained socked in, landing conditions still below minimum allowances, and the tower personnel said we could "try and come on in, but we would not recommend it." So, following our instrument landing pattern to the letter, we saw nothing but those instruments on the panel until we were about one hundred feet from the end of the runway. I bounced it in, came to a stop and climbed down that ladder to the adorable ground and gave it a hug. It looked like heaven on earth. I was so scared I wasn't able to eat a thing - not even those delicious fresh eggs.

While at Mohanbari we did more than just fly the Hump. We had lots of free time in between flights and our time was, for the most part, our own. My three basha mates and I were close friends, we all got along together. It was nice to have a captain in our group because with his rank, he could get us a jeep to use just about anytime we needed one. He was also a good bridge player. Harry had been a baseball player in high school, so we played lots of catch and played on the officers' baseball team, when we could find another team to play.

Boswell was a nice guy, and was willing to do just about anything any one of us might think was a good idea to do. We went on a tiger hunt once together in a weapons carrier (a small truck) with some machine guns and Carbines (rifles), as well as our forty-five pistols. We all had accumulated some R&R time and decided to hunt tigers and head towards Rangoon, in Southern Burma. We tore up a bridge in a small village with our truck trying to cross a river, and had to hire an elephant and its owner to come tow our truck to shore. We also had to pay some village big shot for the bridge. We never saw or even heard about any tigers, but we saw lots of monkeys and killed a couple of porcupines.

The best recollection from that trip was our stay at the British Hospital complex located along the Road to Mandalay. The commanding officer was a British major who had been there for three years, and had a few fellow officers (and sometimes none) to help him. He relied on the local help to assist him. The area had been held by the Japanese in the past and he took over when they were finally driven out by the Gurka Guards, a fierce group of fighting Indian soldiers whose reputations were enough to make any foe panic. They fought mostly at night and couldn't ever be located in the daytime. They hardly ever fired a shot, and never took any captives. Their victims were usually found the next day with their throats slit while still in bed, or found dead at their posts. Well, this major loved to play Monopoly, but none of his "help" knew how to play. So, he insisted we four should play with him, in exchange he said, for all the gin and tonic water we wanted. A deal was soon reached, and we played for three days. I don't remember the major ever going to bed, but I know I passed out a couple of times from all the gin and had to sleep it off.

We also took a trip to Shillong together. This entailed a flight from Mohanbari to central India, and then a truck ride up into the mountains, into the city of Shillong (5,000 feet high), and some cool, cool weather. That was the best part of the whole trip, cool weather both day and night. We stayed in an English hotel with several English guests, owners of tea plantations, who wanted to get away from the heat as much as we did. The only difference was they stayed the entire monsoon season and we stayed for two weeks. The food was all fresh, the beds had mattresses and springs with linen sheets, and we had our own bathroom in our rooms. There was a golf course and tennis courts, as well as a horse racing track. I didn't play any golf or tennis because my basha mates weren't into it, but we did go to the race track a couple of days. The odd thing about the track was, it wasn't level. Halfway around the track the horses went out of sight as it dipped below eye level and, just about every time, the horse that had the lead going out of sight was not in the lead coming back into sight.

It was joy at hearing about Japan's surrender in World War II while midair, at about 16,000 feet, in August 1945.

While the war ended in August, we were not sent home until late November in 1945. Mohanbari was gradually shut down following the defeat of Japan, and all personnel and equipment was moved to Calcutta, at Dum Dum airport. I made a few flights from there, but on the whole, I wasn't much interested in flying anymore. I just wanted to go home.

While awaiting shipment back home at Dum Dum, I did, however, volunteer to make two round-trips to Shanghai. The first was shortly after the war was over. I took a group of soldiers, who had been in India for years, to Shanghai to catch a ship home to the USA. When I arrived in Shanghai, the Japanese had just vacated the airfield and the barracks were Japanese style, short beds and short shower heads is about all I remember, and a quart of saké was ten cents American. When I came back about a week later it was one dollar American. The fleet had landed, I was told, and raised hell with the price of everything. Old supply and demand at work. There was also a bar called The Atomic Club, owned by a group of hoods from Chicago, during the Al Capone era, who were there to escape the law in the USA.

On December 5, 1945, finally it was time to go home! I had requested to return to the US by ship via the Atlantic Ocean route through the Suez Canal. I left Calcutta on a ship that sailed first to Ceylon (Sri Lanka now), and eventually the ship arrived in New York and Camp Kilmer on New Year's Eve. Later, I was sent to Ft. Lewis and arrived back home in Seattle on January 18, 1946. In my time in theater, I had made eighty-one trips over the Hump, flying 582 hours over that rock-pile (I missed receiving a Distinguished Flying Cross by 18 hours as 600 was the magic number). I was discharged from the Air Corps on March 18, 1946, after using up my accrued leave, weighing 185 pounds.

-=-=-=-=-

After the War, Dick completed UW Law School in 1949 and passed the Bar exam while teaching flying at both Taylor and Kurtzer (now Kenmore Air) Flight Schools. He was a respected trial attorney for decades and built a successful law practice that spanned 52 years, including several years as both Assistant United States Attorney and Seattle Municipal Court Judge. An avid handball player, he also managed to keep regular court times at the Elks and Washington Athletic Club (WAC), playing well into his 70's. True to form, Dick had incredible recall of some interesting legal and political times in our local/national histories and shared just enough to fascinate his children and friends, "over and over in all the best ways." Dick and Bea's lives were full, with family, friends, and travel. Dick lived an exceptional life. He had a strong set of values, with a moral compass rooted in his Catholic faith, and served is country earnestly in WWII. Dick stayed involved in numerous projects and organizations even in later years, which of course included the Hump Pilots Association. His was a big personality, and well remembered: "Our Dad was a formidable presence. Everyone wanted his favor, and you felt lucky to have it. ...AND one more of his famous martinis (an 'efficient' blend of Tanqueray and Vodka, but never before 5:00 pm)."

Richard Daniel Harris passed away on March 3, 2020, at 98 years old.