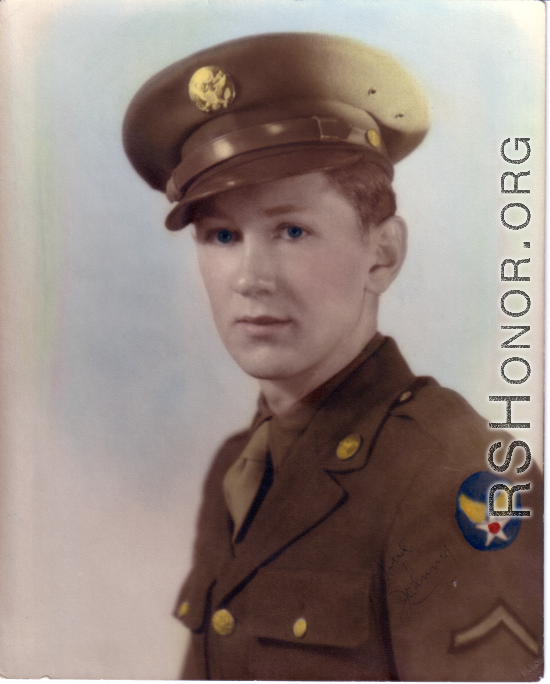

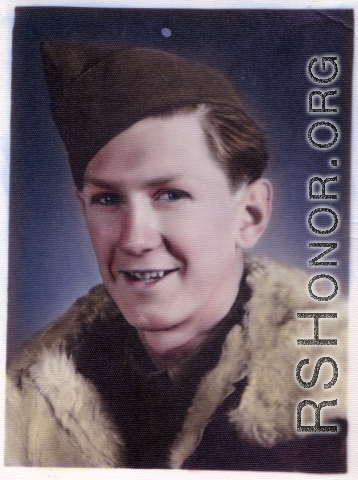

John Jacob Gerber in uniform and with Army Air Forces WWII Shoulder Patch, in hand-colored image.

John Gerber, born February 24, 1924, served in the 322nd Troop Carrier Squadron in the CBI during WWII. John Gerber finished 12th grade at Hinckley High School, in Hinckley, Ohia in 1942, then worked a half year at Thompson Aircraft, in Cleveland, running a lathe and doing mechanical work. After enlistment on November 6, 1942, then two months basic training as a private, and further 6 months initial preparation as a corporal, studying airplane and engine mechanics in locations such as Amarillo, Texas, adn Burbank, California. He did 6 months as military police stateside, carrying out guard duty and patrolling part of town. Later he did 15 months as an aerial engineer in the CBI, flying as "Crew Chief" chief engineer of a C-47 transport plane, in charge of repair and maintenance of engines and entire aircraft. He left the service on October 16, 1945, with the rank of Sgt.

During this period he also fit in starting a family--getting married on September 3, 1943, and having a first child, a daughter, born September 1, 1944.

Hi, these are the memories of my time in China. These are my memories as best I can recall them. I tried to stick to the facts as they happened. I did not try to embellish them or to take away from the dumb things I did. It happened that way and I told it that way.

-Written by John Jacob Gerber, 322nd Troop Carrier Squadron, for the Remembering Shared Honor website in 2003.

War Time Duties and Events

My barracks assignment reunited me with many of the men I had gone to training schools with prior to being sent overseas. Most of these men had been in my class at Lockheed Aircraft Corporation in Burbank. Some of them had even attended my wedding others were also stationed in Kunming, China, while still others had been assigned to fighter or bomber squadrons at other bases. Robert (Bob) Jolley, who participated in our wedding, met me when I checked into the barracks. He took me around the area and showed me the things I would need to know. He also informed me of the air raid warning system and the procedures we were to follow in the event of an air raid warning. He told me that if there was an alert, we were to immediately report to the flight line to help get the aircraft airborne before the enemy bombers arrived.

Well, I guess you know we had an alert that night. Sometime in the early morning Bob woke me up and said “Let’s go, we have a three ball alert.” The alerts were as follows. A one ball alert meant enemy was in the air and may be heading our way. Two ball alerts meant they were definitely coming our way and it was time to move. A three ball meant bombs could fall at any time. We were already in a three ball alert. We jumped into a jeep and arrived at the plane dispersal area in a few minutes We waiting about 20 minutes, and since no one else had shown up. We were about to leave when a jeep roared into the area. Bob and I immediately ran over to where we had seen the jeep but could not see anyone. It was extremely dark. I remember shouting at Bob “Here’s the jeep but I don’t know where the son of a bitch went.” I immediately heard a voice from the nearest plane stating “Colonel son of a bitch to you and I’m over here.” We later learned he really was a Colonel. Colonel Williamson, Squadron commander and very close personal friend of General Claire Chennault. They had flown together for many years prior to war breaking out with Japan. Once again it was “open mouth and change feet time.”

Then Col. instructed Bob and I to pull the locks and pins and prepare for take off... I pulled the Rudder and elevator locks and Bob was to have done the rest. The Col. climbed into the pilot’s seat and Bob into the copilot’s seat. While the Col. was fastening his seat belts I reached up and turned the ignition switches to the on position, to facilitate engine start up. At this time I got a whiff of the colonel’s breath. It smelled like pure vodka. I recall thinking this guy is smashed and we will probably never get off the ground. I was thinking this would be the shortest “flying” career in history.. When the Col. was strapped in, he reached up and turned the switches off and said start engine 2, which controls the hydraulic system and therefore the brakes, flaps etc. Of course it wouldn’t start. I tactfully suggested that the switches were in the off position. He almost bit my head off when he shouted “I just turned them on don’t tell me they’re off.” So I suggested that perhaps the mechanics had installed the switches in backwards. He bought it. “Saying lets try it.” Of course the engines started right up. As soon as the engines were both started he swung the tail section around and headed across the taxi strip, He gave the cold engines full throttle and roared across the ground between the runway and the taxi strips. . I remember thinking that mine was going to be the shortest military career in history. As we picked up speed, we must have reached take off speed because I remember bouncing once and when we hit the ground and bounced again he said wheels up! I thought oh no we are going to bounce once more only there won’t be any wheels to catch us! However, in the military you are taught to follow orders instantly, at least in the military then, so without hesitation I pulled the lever to raise the landing gear. It came up and we were airborne, much to my surprise.

For the next hour and a half, we flew around among the mountain canyons trying to stay hidden from any enemy aircraft. Troop carrier planes were not armed therefore we could not engage enemy aircraft and had to hide from them. He flew at an altitude of around two hundred feet above the ground in and out of the canyons. After the hour and a half he gained some altitude and then asked Bob “Which way is the field?” Meaning our air base. Neither Bob nor I knew. He was the one who should have watched the direction we were flying. He then instructed Bob to get on the radio and find out. Bob informed him he was a mechanic and not a radio operator and did not know anything about frequencies etc. He then asked me and I told him I too was a mechanic and had just arrived in China that afternoon before the raid. At that time we spotted a dot in the distance. The question of course was “is it one of ours or one of theirs?” The Col. decided we had better go see. Fortunately it was one of ours and we simply followed it back to our base. Prior to landing, the Col.“Buzzed” the tower. After landing, as we were departing the plane he said “the next time you fly with me pull all the locks.” He had been flying with the aileron locks in place. Bob had forgotten to pull them. Ailerons assist the pilot in making the plane turn while in flight. It takes an exceptional pilot to fly as he did with those locks in place. It really was a most interesting first day for me.

Well, later in the day I was assigned to a plane as a flight crew member. I did not know any of the others assigned to that aircraft. The assignments to aircraft were the mechanics always worked and flew on the same aircraft. The pilots however, rotated from one aircraft to another. So everyone always knew who the mechanic was on any given airplane, no one knew who the pilot would be until just before flight time. I suppose this gave the pilots an opportunity to fly the good planes too. My entire time in China, to my knowledge, we never lost a plane due to mechanical problems. We did lose too many but they were due to the war and stormy weather, I was very lucky. In fact looking back I know I had a guardian Angel watching over me the whole time. I loved flying. I was always ready to take anyone’s turn that did not want to fly on any particular day.

Shortly after my arrival I came down with malaria. After leaving the hospital in Calcutta, India, I traveled by train to Chabua Air base. I traveled in the same car with four British soldiers. One Limey, one Cockney, One Aussie, and one Canadian. The only one I could converse with was the Canadian. I couldn’t understand any of the others. I had an abundance of “K” rations, which were pretty good. I readily shared these with my four new friends. Since I had just been discharged from the hospital, I was very thin and still weak. Each time the train stopped, which was quite often, one of them would grab my helmet, it was the biggest, and run to the engine and draw a helmet full of hot water and come back to the car and brew tea for all of us. Whenever the train stopped for mess call, we had to be very careful as there were hundreds of birds, either crows or ravens that would swoop down and take the meat right out of a mess kit. I was lucky and never lost any. During this train ride I fell asleep one afternoon without wearing a shirt. When I woke up I was covered with mosquito bites. As a result I came down with malaria two weeks later. I had malaria at least twice while in China.

I was assigned to a plane as one of the three man crew. Nothing of importance happened during the next few months. We were constantly hauling supplies to the other bases throughout China. We were actually losing the war with the Japanese at this time. We hauled supplies to some bases and evacuated other bases. About three months into my “flight career,” one of our planes , a C-47 (also known as the “Gooney Bird) developed some engine problems at a forward base I believe it was Chickiyang but am not certain. The engines were out of sync and their crew could not fix it. For whatever reason, I was sent up forward flying up as a passenger on another C-47 hauling supplies there to fix it. When I arrived it only took a few minutes to determine the engines were out of time. I just pulled both magnetos and set the number one cylinder and replaced the magnetos and within a very short time had both engines purring like a fat cat. I called the pilots and told them their plane was ready to go. When we returned to our base, I was summoned to headquarters and asked what the problem had been. After explaining what I had done, I was informed that as of that moment, that was my plane and I was given “Crew Chief” status. That for someone who was “too tall to fly.” I now had my own plane. I also had a crew of three who did not like to fly. They only wanted one flight per month to maintain their flight crew status and flight pay. This was fine with me as I loved flying, probably made even sweeter because I had been told all along that I would never fly because of my height (still 6’ 8”). I took all the rest of the flights each month. I also decided I was going to make the air force my career. I just plain loved flying.

One of my favorite pilots was an American Indian. His last name was Harrington, can’t remember his first name. So naturally we called him Chief Wahoo, after the comic strip. He was short but he could fly! He and I became good friends. He taught me how to throw my trench knife and we competed with the .45 pistol. On one evacuation shuttle run [during the Japanese Ichigo campaign of 1944], we were again the last plane out before the field was to be destroyed by the engineers, I do not recall the name of this base, I do remember the general, though, as you will understand after reading this. As the coolies were loading our plane, Chief Wahoo and I walked around behind the barracks to look around. We were going to see a lot of military equipment burned and blown up because there was not time to move it. I do recall the fact that all sort of military equipment, such as spare engine parts, small arms, clothing and other vital supplies were being destroyed while we were hauling personal furniture, instead of at least one more load of supplies, before the base was destroyed. The Japanese were only about three miles from the base and coming fast while we could not hear or see the actual advance, we were willing to take the general’s word for it rather than go see for ourselves! What was being loaded however, was General Vincent’s personal furniture such as his refrigerator, bedroom set, living room furniture etc. and all his possessions he had accumulated over the period he had been in charge there. Anyway, Wahoo and I began to argue as to which of us was the best shot. There was a telephone pole about fifty yards away and we decided to shoot at that. Wahoo took the first shot and after about a part of a second we could hear the “thunk” as the bullet actually hit the pole. That’s a long shot with a forty five automatic. Well. Wahoo put his pistol back in his holster and I drew mine. At that point in time, General Vincent came running around the corner. As he drew near he shouted “WHO FIRED THAT SHOT?” Well now, there we stood and I was the only one with a weapon in my hand!. He literally screamed at me that if I wanted to shoot my pistol I could be taken three miles away where the Japanese were and could shoot it all I wanted to. Then he proceeded to chew me out royally. In the meantime, Wahoo had gotten behind the general and was shaking his fingers at me like you would to a naughty little boy, shaking his head like I had really done something terrible and the world was going to end right there. Think about it I was being chewed out be a two-star general and Wahoo was so funny I had a problem not laughing. He knew I would never deny firing the shot and since I hadn’t even been asked, we didn’t have a problem at all. After the general left, Wahoo laughed and asked If I still wanted to know who was the best shot? Oh well, those are the kind of chewing’s that heal right away. Just a couple of memories.

As stated before, in 1944, we were losing the war with Japan. Our squadron was in thirteen evacuations where we gave up our air fields and burned all the supplies we could not get out in time [during Ichigo]. Several times my plane was the last one out and after our takeoff the Army engineers blew up the field, runways and buildings along with the supplies. While we were sometimes the last plane out of the soon to be destroyed bases, the engineers and the last of the Chinese labor forces left after we did. Once the engineers had destroyed the base, they left in their land vehicles. I’m assuming they were military vehicles able to travel in rough terrain.

We rarely flew at night except for supply drops. These were necessary military supplies to be air dropped to the Chinese forces battling the Japanese army. However, on several occasions these supplies were actually dropped to the Japanese army as they had advanced further than anticipated. Since the drops were made at night, map coordinates were used so the air crews actually did not know where the Chinese troops were and made the drops based upon the latest information available.

Whenever I was not flying in the evening, we would go to the nearest town and have a few beers and a better-than-mess-hall meal. Once in one of the forward bases, I believe it was a place called Chihkiang [Zhijiang], as we returned from town and approached the airfield, all the runway lights were on and so were some of the barracks lights. This was early in my China career, I’m guessing sometime during the time frame of March maybe through May. I’m just not certain when. As we started to cut across the end of the runway toward the barracks, a string of bombs went off right along side of us but toward the center of the runway. Guess you know we all bailed out of the weapons carrier we were riding in and jumped into a hole a few feet away. This was my first actual bombing and I wanted to see more of it. I stood up to get a better view and my buddy, Bob Jolley, told me I had better sit down as there were snipers in the hills. As I bent forward to see where I would be sitting there was a smacking sound behind me and a clump of dirt fell out of the bank . I had been targeted and the bending over had saved me. I did not stand up again. After the raid was over, we piled into the weapons carrier to ride back to the barracks and found the right front tire had been hit by shrapnel and was flat. It was an eye-opening experience.

Another time we had received a shipment of coveralls, the problem was there was only one size. Large. One of the guys on my crew was “Porky Patrone” about five-five and Mr. five by five. He took a pair of coveralls and cut the legs off just below the crotch and put them on. He was so funny, he looked and walked like a penguin. In the middle of his showboating, we had an air raid. Well when Porky tried to run, he pulled one foot out of the pant leg and stuck it down into the other and went end over end. . He looked so funny, we helped him to get out of the barracks but he never put them on again. No one got hurt in the raid, that is except Porky’s feelings. There were some fun times along with the realities of war.

One night while sitting in a restaurant in Kunming perhaps about six months or so after my arrival in China I met another soldier, name unknown at this time. In the course of our conversation he informed me he was General Claire Chennault’s personal baker. He also told me the General’s favorite pie was chocolate cream pie and that he, the baker, was having a terrible time getting enough chocolate to make the general’s pies. I told him I could get him all the chocolate he wanted ( I could do this as sometimes when we evacuated a base we would be able to “liberate a few cases of K Rations. Each box had a bar of chocolate included with the rations). We made a deal I would supply the chocolate and he would bake me a pie a week when he baked for the general. This arrangement lasted until I was rotated to the states. Since I was doing so much flying, there was always the possibility that I would not be at Kunming when he brought the pie. So I told my crew that if I was away from the base, they were to check my locker on pie day. If there was a pie they could have it. I did not want the baker to ever bring me a pie and still have the last one in my locker. It never happened. My crew thought they had died and gone to Heaven on pie day if I was gone. When I was there we all shared.

When I arrived in China, the rotation policy was ground crew thirty six months and air crew personnel eighteen months. This I had not known when I reported for “flight duty” But since I was a very excellent mechanic and loved flying, I don’t think anyone was interested in grounding me. Since many of our flights were over areas controlled by the Japanese or were in areas where we had a good probability of being seen by Japanese air patrols, and since we were flying unarmed transport planes, these areas were considered as “combat areas. Whenever we flew through these zones we were credited with combat hours. Our vulnerability was very great. If we were seen, we were gone. Since I was doing most of the flying on my crew, I soon earned enough combat hours to be awarded the Air Medal.” Jumping ahead a little, it wasn’t to much longer until I was awarded The Distinguished Flying Cross. A few more months and I was awarded an Oak Leaf Cluster for my air medal. This was the same as a second Air Medal. I was quite proud of these accomplishments. If I had stayed another couple months I would have earned an Oak Leaf Cluster for the DFC.

When I left the hospital in Calcutta, my nurse and good friend Lieutenant Edna Fieldhauer, had given me one of her nurses pins/insignia for good luck. Since she was an officer and I was an enlisted man I could not wear the pin in plain sight so I pinned it on the inside flap of my left shirt pocket, over my heart. This way I always had it with me. Although I was not superstitious, in war time, I remember thinking oh well, it can’t hurt. I know she believed it would help me. I always seemed to remain safe and unhurt and of course gave the credit to her pin. While entering my plane for a flight one day, I tried to rub the pin as I always did when boarding. It was gone. I don’t know where or when I had lost it but it was gone. Unbelievably I was less carefree than usual for the next few days while flying. Then with several days of successful flights under my belt again I kind of forgot about the lucky pin and only felt sorrow for having been so careless as to have lost her last gift to me. I really admired and cared for her a lot. So much time has elapsed since all this happened, I am sorry to say I don’t remember what she did after the war. I do not believe she stayed in the service but it seems as though she continued in the nursing field. As I write this on April 28,2003, I can still very vividly see some of the events I have described.

During one evacuation period, we were making very short shuttle runs trying to get as much equipment out as possible before the Japanese overran a facility when one of the crew, Porky Patrone, asked to take the remaining flights as he did not have his time in for the month. Of course I agreed to let him go. Flight pay was fifty percent of the base pay and no one wanted to lose that much money. Well Porky was about five by five and weighed around one eighty. I was six eight and weighed about the same. His first flight of the day ended in disaster. The plane was crunched. , I do not remember what happened other than the plane was severely damaged. I have tried to remember what went wrong but my mind is a blank as to the details. I wished I could recall. Had I been on board in my usual station I could have been severely injured because the cabin was crushed in and any tall person would have sustained considerable head injuries. Porky was short enough he escaped injury. This incident along with others I will talk about, gave me the feeling that I really did have a guardian angel watching over me.

Our airbase was fourteen miles from the nearest town, Kunming, China. In 1943, it was a typical small town in China. Actually the first town encountered from the Burma trail. A quick note, I happened to not be flying one day and so was able to be sitting on the roof of our barracks when the trucks from the first convoy over the Burma Road entered our area. That really was a special occasion. Kunming’s streets were dirt and narrow, with hardly a break between the many buildings Of course there was a town privy; it was in the center of the intersection of the two main dirt streets. It had

Walls about four feet in height and ditches for the populace to “go” in. The little children were better off. They had the bottoms cut out of their pants and all they had to do was to squat and go. This was the big city of Kunming.

There were however, several tolerable restaurants in the town, lots of bars and nightclubs catering mostly to the service personnel. At one end of the town was a French mission. In my wanderings, I happened into the mission one day and was amazed at the beautiful needlework the good sisters did. I was so impressed I ordered a large pure white silk table cloth and twelve matching napkins with red dragons embroidered upon them. The cost was forty dollars American. Each time I was able to come to town, I always checked on the progress of my tablecloth set. To get to the mission was easy. Just jump into a rickshaw and tell the coolie “French Mission.” And in a few minutes I would be at the mission.

During this period there were a few incidents that I was not involved in, such as service people getting drunk and shooting up the local bars etc. This happened often enough that a regulation was passed prohibiting the carrying of firearms when entering the town areas in China. This during war time. Our commanding officer (CO), was still Colonel Williamson, a very close friend of General Claire Chennault of the Flying Tigers Fame, and when he read the order he instructed us to wear our side arms when traveling into town. He insisted on at least one side arm in each group. I felt much better going armed than disarmed as there were snipers in the area. One day shortly before my rotation home possibly around January or even February of 1945 I went to check on my table cloth set and as instructed wore my forty five automatic in a shoulder holster under my flight jacket. When I selected a rickshaw and got into it, the coolie was the biggest coolie I had ever seen. He was at least six foot three inches tall and weighed about 200 pounds of solid muscles. They only wore a breech cloth around their middle and so all his muscles were visible. I had never seen a man with such muscles all over his body. No fat at all. I had to admire the absolute beauty of his physical body. I told him “French Mission” as I always did. It wasn’t long before I realized we were going a different way than I had ever gone before and that I was in a part of town I had never been in or even known about. There were no shops, restaurants or even bars. I also knew if he was up to something there was no way I could stand up to him. I was not that long out of the hospital and even when I had been in my best physical shape I couldn’t have even had a chance at taking him. It dawned on me that it was time to get some help. I drew my .45 from the shoulder holster, took an extra clip out of my pocket, in case he had friends to help him, and since I always carried a round in the chamber, I pulled back the hammer cocking it and resting it on my knees, pointed it right at the small of his back and I recall thinking…if he makes any sudden moves such as dropping the rickshaw handles and turns around and takes one step toward me….he is dead! It was only a minute or two later that he pulled the rickshaw into the mouth of an alley, dropped the rickshaw handles and turn around with his right hand going into the sash around his waist! His eyes got big as saucers and his raised foot stayed right where it was when he saw the .45 in my hand pointed right at him. If his foot had come down toward me he would have died on the spot. He put his foot down where it had come from, fumbled around inside his sash for a few seconds and came out with a cigarette in his hand and asked “You got light?” I said “No light. French Mission.” He got the message. In a few minutes we were at the mission. Unfortunately, the good sisters informed me that I did not have a table cloth or napkins and I had never ordered one. It was strange because all the other times I checked they told me it wasn’t quite finished. Apparently some one had offered them more money. I wasn’t able to get one made before I rotated home.

The incident with the rickshaw coolie bothered me for years. I often thought I had made a terrible mistake in not shooting him. I wondered if he had tried the same thing with others who were not as prepared to deal with that type of situation. Was it possible that because I did not shoot him I had allowed him to try again with others? There were frequent incidents where servicemen were found dead and the cases were never solved. Could he have been the one? For me I was glad I had not taken his life. For his other victims, if any, was I partially to blame for their deaths? It was something to think about.

Memories of wartime and the things we did and the things that happened to us seem to come in stages. Most of my memories are good ones. They are like the ones you have read to this point They are important to me because I lived them. I’m not so sure that those of you reading them will find my stories as interesting as they are to me Probably not nearly as exciting as a war movie or a tape. Anyway, I have been encouraged to continue so here goes. These are my memories and again I’ll say I neither try to embellish or detract from them. They are told as they happened.

Actually while sitting here thinking about it, a few more incidents come to mind. My introduction to the most popular alcoholic drink was rather interesting. Upon my assignment to a barracks, several of the other airmen came over, introduced themselves and asked me if I cared for a drink. Of course I said I’d really like one. At that point one of them, unknown at this time, fixed me a drink which was mixed with grapefruit juice, several of the other also had one. As we were about to drink it, another airman came up and said something along the order of, as long as your pouring, I need some for my cigarette lighter. Some of the “alcoholic” beverage was poured into his lighter, he lit it a few times, said thanks and left. About the same time another airman arrived and stated he had some grease spots on his shirt and to pour a little on a rag so he could get the grease out. They did and he did. Of course this was all prearranged to let the newcomers know they were drinking some really potent stuff. But you know it tasted great and it did have a kick to it.

One of my friends shortly after my arrival in Kunming, a Sergeant Carl Spangenberg, introduced me to a family, Paul and Audrey Braga and their three children. Francis (Bunny), the oldest girl was six, and a very beautiful child. The next was a three year old son and then a brand new baby boy. Going from memory after all these years, I don’t know for certain what the boys names were, I think Paul and Michael but am not certain. They were refugees from Shanghai where they had owned a business. Paul was English; Audrey was half English, a quarter Chinese and a quarter Portuguese. She had the best of each and was a strikingly beautiful and very intelligent woman. They were trying to get to America where Paul had a brother in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Paul and his family lived in a house on the base, away from the flight line. It was a one room house, dirt floor, with cheese cloth over the windows instead of glass and was rented to them by the American Red Cross. They were a really nice family and we became friends right away. Carl and I would go through the mess halls and dump all the sugar bowls into a sack, “confiscate” some flour and then head over to the Braga home. Audrey would make donuts and fudge and we would sit around playing a card game called “Touring.” It was an interesting fun game. As time went on we became very good friends.

One evening Paul came to me and said he needed to talk to someone about a problem they were having. The house they were renting from the Red Cross, as stated before, had dirt floors, cheese cloth window coverings, no indoor plumbing and just basic furniture. He informed me the Red Cross had presented him with a bill for the rental. It was for four hundred dollars per month for four months. I remember telling him, that’s only sixteen hundred dollars for four months. In real money, that’s only sixteen dollars American. The rate of exchange at that time was four hundred Chinese dollars for one American dollar. He then informed me he was talking about American money! It was outrageous. Our Red Cross taking advantage of refugees. He told me that they really did not have the money and he did not know what to do. I told him I would see what I could do for them and let him know in the morning. The next day I told Paul to have his family at the end of the runway at daybreak the next morning with everything they had they could carry. I had made arrangements with one of our pilots who was a good friend, to fly them into India and from there they could continue their journey to America, The pilot, and his name escapes me at his time, was able to do this because we did not tell anyone about it and no one knew except for the crew, the passengers and me. He was also reminded to not worry about the bill to the Red Cross. Most servicemen/women from the world war two era did not like the Red Cross at all, the above being one of many reasons. The following morning we all met at the end of the runway, loaded their possessions on the plane and said our good-byes. We never expected to meet again because he was headed for Milwaukee and I would have my home in California. I intended to stay in the service because I loved the life and I loved flying. [Eventually they did cross paths in the US many years later.]

When I first arrived in China, I was informed the rotation system for flight personnel was eighteen months and for ground personnel thirty six months. Along about March of 1944, the system was changed. Anyone having four hundred or more combat hours would be rotated stateside in one year. At the time I had over four hundred and fifty combat hours. My papers were put in and I was homeward bound a few days. At this time I must add that when I first realized I was eligible to go home, I was excited by the prospect. I was very fortunate in that I loved my job so much, I had never been homesick. Also if you recall, the other three members of my crew did not like flying and therefore, once they had their four hours per month in, they very kindly allowed me to do all the rest of the flying. I guess another reason I did not get homesick was that my lovely wife wrote to me several times a week and I had tons of letters, and lots of pictures of my new daughter, whom I still had not seen as she was born while I was in China. She was born on September 1, 1944, just two days before our first wedding anniversary. However, when I realized I could go home and that I would get to see my daughter for the first time, and also be reunited with my very lovely wife, I guess I just wanted to go home. I did think about staying over long enough to get my oak leaf cluster to the DFC, but decided that maybe that would be tempting fate a little to much and so I decided it was time to go home.

-Written by John Jacob Gerber for the Remembering Shared Honor project. Edited by Patrick Lucas.